“I saw Holy Jerusalem, new-created, descending resplendent out of Heaven, as ready for God as a bride for her husband.” Revelation 21:2 (The Message)

The earrings dangle from my ears, pierced through once-closed holes by my soon-to-be sister-in-law. The old, golden necklace hangs from my neck, its ornament matching the one on my earlobe. The engagement ring, once a trinket of my soon-to-be husband’s great grandmother, rests quietly on my finger, anxiously awaiting its partner. The bodice and Spanx hug my body, sucking everything in, hopefully in a not-too obvious way. The headpiece pinned onto my head sparkles in the afternoon light with its golden bangles, and the veil is tucked neatly into the mountain of bobby-pinned curls. My eyelashes are darkened by touches of mascara. The eyeliner and pink eye shadow bring out my dark eyes. The pink lip gloss brightens my lips. Everything here highlights what is already there naturally instead of hiding it all away or making it into something it’s not.

The large bouquet is composed of home-grown wheat and flowers plucked from the shelves of Michael’s. The lace dress with matching sleeves to mask the fact that it used to be strapless is simple but elegant, if I may say so myself. A bustle hides behind the gown so I can lift it up to dance the night away, and I will kick the golden wedges on my feet off the moment pictures are done.

It’s not a resplendent get-up. But damn, do I look beautiful. And for once in my life, I feel ready.

“One of the Seven Angels who had carried the bowls filled with the seven final disasters spoke to me: “Come here. I’ll show you the Bride, the Wife of the Lamb.”” Revelation 21:9

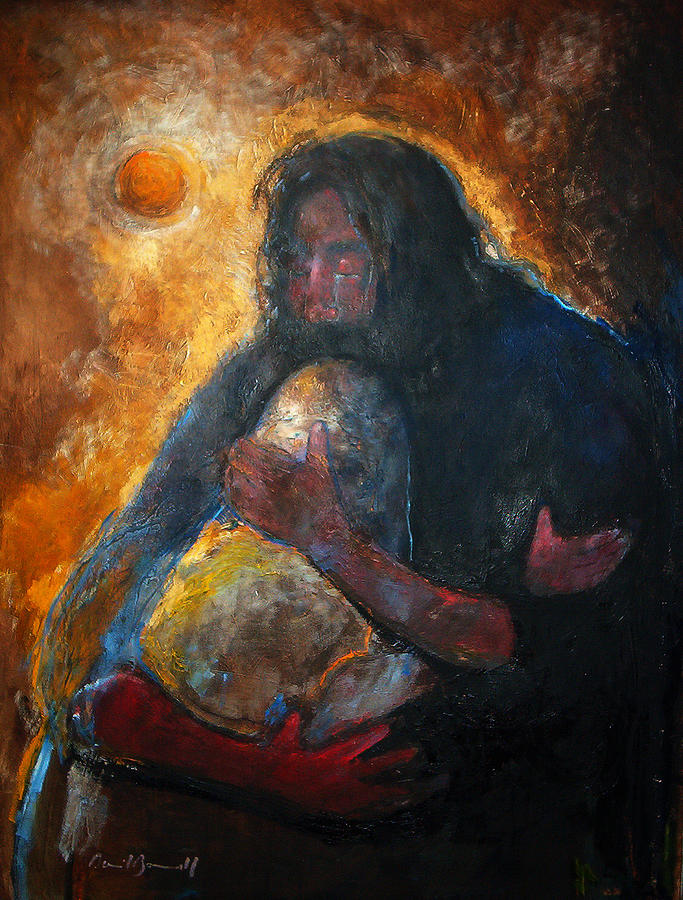

The harbinger of death, destruction, and apocalypse suddenly becomes the doting parent of the bride.

Both of my parents attended and played significant roles in our wedding. Mom walked me down the aisle, and Baba prayed a blessing over me and my husband. While both of them are in my life right now, Baba insisted that my mother be the one to, for lack of a better phrase, “give me away.” She raised me, after all. I know it. She knows it. Baba knows it. The whole family knows.

It was she who walked me down the aisle as she has walked with me my entire life. It was she who took my hand out of hers and placed into the waiting hand of my husband, symbolizing a transfer from one family and one partner to another. She kissed our cheeks and told us she loved us, welcoming her son-in-law as her own and leaving me behind to make a new life with another instead of her. She went to her seat and watched us exchange our vows and promises to one another, and she came back up the aisle alone.

For years, it was me and Mom against the world. It was our home that sheltered, nourished, and emboldened me to make my own. It was us that weathered apocalypses together, who stared into dark secrets uncovered in our lives, saw the people we loved exposed in true form for better or worse, saw dreams die and new ones born, grappled with fears and insecurities and lived into our strengths. We weathered the despairs and joys together.

And that day, she put my hand in Bryce’s as a way to say, “Go, and do likewise.”

“Look! Look! God has moved into the neighborhood, making God’s home with people! They’re God’s people, God’s their God. God will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death is gone for good – tears gone, crying gone, pain gone – all the first order of things gone.” (Revelation 21:3-4)

I can’t imagine something new coming into the world without tears spilling or laughter bursting.

I didn’t cry on our wedding day. I don’t cry when I’m overwhelmed by joy.

I laugh.

I giggle.

I grin my wide, toothy, ridiculous grin that distorts my face and drives my husband wild with happiness.

My husband cries.

When our friend Makayla read a poem, his lips quivered and his eyes watered, but they never broke contact with mine. As he began saying his vows to me, his voice broke as a sob escaped and he struggled to maintain composure as he got the rest of the words out.

It was my giggles and his sobs that ushered in our union and brought us into the world together.

Will it really be like this when God’s Kin-dom comes?

Is that why we stand when the bride walks down the aisle? To see her into this new world, this new life with her greatest love and joy?

Is that why we cry and laugh and spend so much time, money, and effort on marking these occasions?

Maybe so.

All I know is, if that day brings half of the peace, joy, and overwhelming love we felt on October 14th, we might really be in Paradise again.

Our vows:

“I, (name), do solemnly swear:

To honor and be faithful to you as your husband/wife, partner, and best friend,

To love and embrace you in times of joy and struggle,

And as we learn and grow together,

To stand behind you as your support, in front of you as your leader, and by your side as your equal,

As long as we walk this earth.”