On Shrove Tuesday, (or Fat Tuesday for those adverse to fancy liturgical language), I slid down a slick ramp and busted my left knee open.

I was working in a parsonage office, and my boss brought to my attention that it had started raining, and I’d left my car windows down. I had taken the recycling and trash to the dump on my way to work, and without the cracked windows, my car would have been real ripe for the drive home.

Heeding his words, I grabbed my coat and went a little too fast out the door and onto the small, descending ramp attached to the house.

And I went down. Hard.

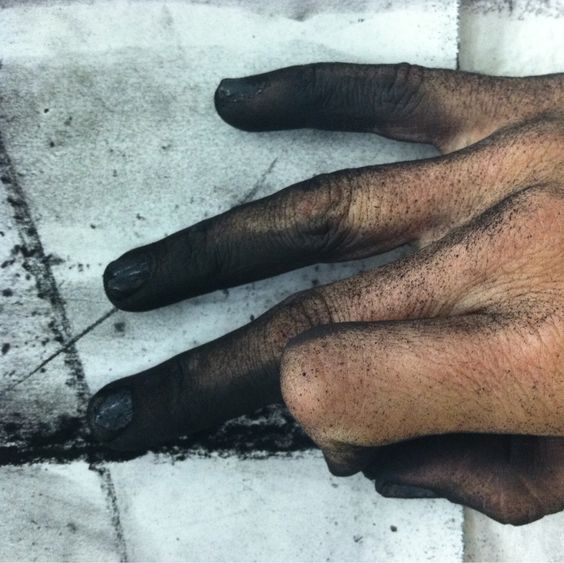

As I recovered from my embarrassment, I bit back curses and gingerly pushed myself up from the soft ground. I could feel the wet blood sliding down my leg and seeping through my favorite pair of jeans, which had, of course ripped. Nevertheless, I hobbled to my car, rolled up the windows, limped back inside, and asked my boss for a first aid kit.

This nasty cut bled through the 3 Band-Aids my boss gave me and 3 more at home.

The next day, Ash Wednesday, my knee stung and prickled as I knelt in front of the altar and the deacon smeared ashes on my forehead in the shape of a cross, muttering, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

On the first Sunday of Lent, after days of replacing bandages and applying Neosporin, small amounts of pus replaced the blood. Kneeling for prayers at my Episcopal service was unbearable, and I was in a constant state of adjusting myself on the kneeling altar.

By the second Sunday, getting on my knees for prayer was a bit more bearable. A hard scab covered the worst parts of the wound, but a small remnant of exposed skin remained open to the environment.

I began to regret being part of a denomination in which most of our prayer time was spent on our knees. We made our confessions crouched over rickety altars. We partook of our holy meal while kneeling. Whenever we asked to be made right with God and for the world to be renewed, we did so in the most submissive position a body can take. And I did so with physical pain simmering in my body.

When you spend a lot of time on your knees asking for renewal, and you’re already in some type of pain or discomfort, the desire for said renewal to happen becomes much more urgent.

*****

I’ve been thinking about my knee and kneeling in light of the American athletes bending down on football fields, soccer arenas, and basketball courts across the nation.

I think about how I knelt in reverence, and how these athletes knelt in protest, and I can’t help but think they’re somehow connected.

When I knelt in painful awareness of my busted knee, I did so out of submission to and reverence of God, with a sense of humility, smallness, and even defenselessness.

I knelt in preparation for, during the receiving of, and while returning from the Eucharist, a communal meal symbolizing Christ’s nourishing presence within us.

I knelt during prayers of confession, wondering why the One who made us and the universe would entertain the notion of letting us approach with our tiny pleas for forgiveness.

I knelt to lower myself before God, in order for the Kin-dom of God to be made real, first in me, then in the world.

Back in 2016, Kaepernick began kneeling down during the playing of the national anthem to protest the system that this country gave birth to, one that allows the police to brutalize and destroy its citizens with no consequences. He knelt, not because he’s not a patriot, nor because he disrespects veterans, but because he cares about the people deemed unworthy and disposable.

Other athletes began to join him. They, too, knelt in defiance of the corrupt ways of our country, and they hoped that in their kneeling, others would be inspired to make a different world possible.

Instead, people lashed out. Instead of clinging to justice, they clung to their star-spangled idol.

Those who are against this movement say they care about respecting the flag and the country, and about revering the lives lost to protect it.

But I don’t think that’s really why they’re upset.

They’re not mad that Kaepernick knelt or that others joined him. They’re mad that he wouldn’t stand to honor the country that disproportionately mutilates and murders black and brown bodies, bodies like his. They’re mad because these “sons of bitches” broke a code of conduct for an inanimate object that idolizes an idyllic lifestyle that exists at the expense of black and brown and other marginalized lives.

Like the Pharisees with their tithes of mint, they give their fair share of salutes and attention but neglect the more important matters of the law: “justice, mercy, and faithfulness.”

But standing for the flag isn’t the reverence those who seek a more just, merciful, and faithful nation need to show. If we are serious, like Kaepernick and his supporters are, about making America a more just nation for all people, we need to show reverence and submission to something greater.

This requires us not to stand, but to kneel.

We need to show that reverence to God’s Dream for the world, in which justice rolls down like water, the wolf and the lamb feed together and a little child leads us all, and we will no longer need written laws, creeds, anthems, or codes of conduct, because the love of God will be engraved into every heart and soul.

It is to God’s Dream that we pledge our ultimate allegiance. Not America. Not the American Dream. Not even the flag.

And it’s an allegiance we show by getting on our knees.

We show that allegiance by kneeling and confessing our complicity in a corrupt system, even when it is extremely uncomfortable and even painful to do so. We show that allegiance by kneeling in front of our siblings of color in submission to their leadership, since they know the way forward better than we ever could.

We kneel to make ourselves open to discomforting change and transformation.

We kneel to say God’s will, not America’s, be done.

Because the truth is, God’s Kin-dom isn’t something we stand tall and proud for as it enters. It’s one that is ushered into the world as we kneel down in submission to its presence and in defiance of the empires of the world.

We kneel, because we owe our allegiance to this Kin-dom, not an prideful, idolatrous, exclusionary, supremacist Empire.